The patient is doing well, but many unknowns remain

Seventy years after surgeons at Brigham & Women’s Hospital performed the world’s first kidney transplant, doctors at its sister hospital, Massachusetts General, announced an accomplishment they hope will prove equally historic: the transplant of a kidney from a genetically engineered pig into a human.

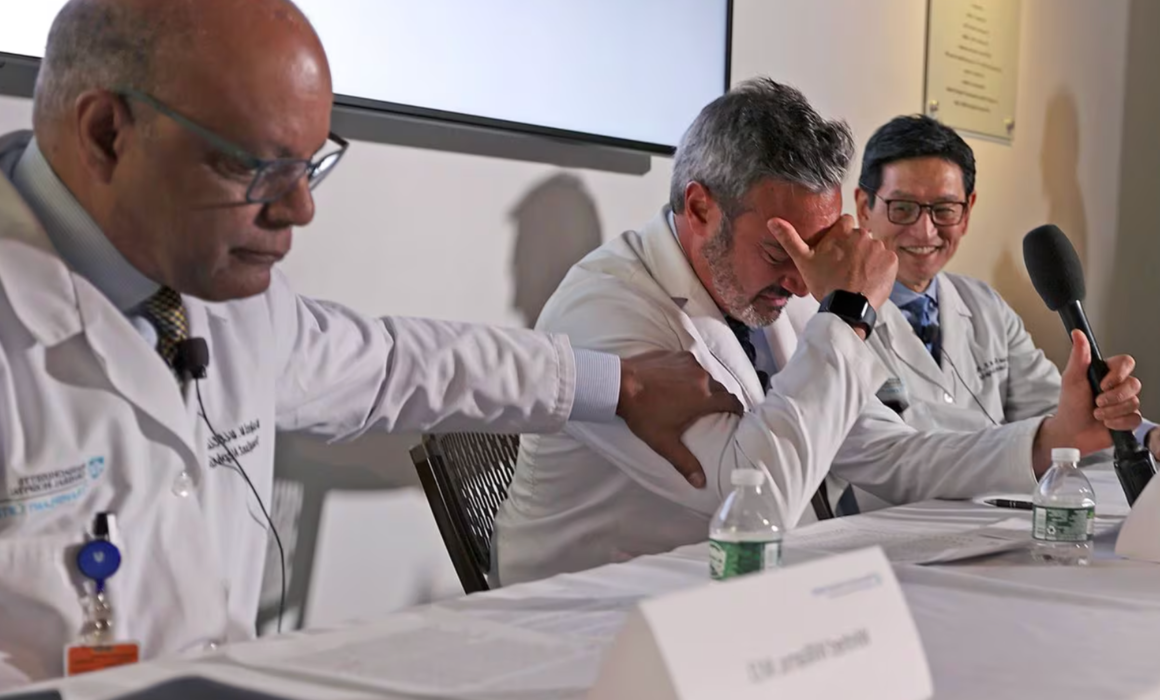

At a news conference Thursday, doctors celebrated the achievement, with one even breaking down in tears as he thanked his colleagues for their contributions.

“Every week we have to remove patients from the [transplant] waiting list because they’ve become too sick,” said Dr. Leonardo V. Riella, medical director for kidney transplantation. “Today we are offering a glimmer of hope to many of these patients.”

The kidney recipient, a 62-year-old Weymouth man, is doing well after the four-hour operation, which took place on Saturday, but only the weeks and months ahead will reveal whether the transplanted organ will continue to work. Doctors will track his kidney function, watch for signs that his body is rejecting the organ, and monitor for infections.

Previous experiments have transplanted pig kidneys in the bodies of brain-dead people and nonhuman primates. In the last two years, two men have received genetically modified pig hearts and lived for up to seven weeks.

This new transplant raises hopes for an alternative source for scarce organs, especially kidneys. More than 100,000 Americans are on waiting lists for organ transplants, and 17 of them die each day, according to the US Health Resources & Services Administration. And people of color have an especially hard time finding matching organs, leading to inequities that a supply of animal organs could correct.

“The dream of transplant researchers — the Holy Grail — has been to use pig organs to supplement the human organs and to solve the problem of the organ shortage,” said Dr. Joren Madsen, director of the MGH Transplant Center.

The human body will reject an ordinary pig organ within minutes, Madsen said. The Mass. General team, after years of research, overcame that obstacle by using a pig whose genes had been altered to make its organs less likely to be rejected, as well as new medications that specifically tamp down the immune response against pig tissue. Still, the prospect of rejection remains the doctors’ prime worry.

Riella said his ultimate goal is that dialysis — in which a kidney patient’s blood is cleansed by machine — will only be used as a temporary measure.

The Food and Drug Administration approved the transplant procedure and the new pig-specific immunosuppressant medications under its “compassionate use” policy allowing experimental treatment for people with life-threatening conditions and few options.

The Mass. General operation is another step in research into xenotransplantation — the transplantation of organs or tissues from one species to another — that has accelerated in recent years.

Teams at NYU Langone Health and the University of Alabama at Birmingham Heersink School of Medicine have transplanted pig kidneys into brain-dead people whose relatives agreed to the experiment; in one case the kidney lasted two months. In 2022 and 2023, doctors at the University of Maryland transplanted pig hearts into two men, but both died within two months. And last year Mass. General researchers reported that gene-edited kidneys functioned well in monkeys for an average of 176 days and in one animal for more than two years.

The pigs whose organs were used in those monkey experiments came from Cambridge-based eGenesis, which also supplied the organ for Saturday’s operation and wascofounded by famed Harvard geneticist and bioengineer George Church. The company used CRISPR-cas9 gene-editing technology to make 69 adjustments to the pig genome, eliminating features that would cause the human body to reject it and inactivating pig viruses that could be a threat to humans.

The Mass. General patient, Richard “Rick” Slayman, a manager with the state Department of Transportation, developed kidney failure as a result of diabetes and hypertension, according to Dr. Winfred Williams, associate chief of the renal division at Mass. General and a transplant nephrologist who has known the patient for more than a decade.

After seven years on dialysis, Slayman received a donated human kidney in 2018. A year ago, the kidney failed and Slayman went back on dialysis, which was especially grueling for him because of repeated difficulties accessing his blood vessels.

When he was offered the chance at a highly experimental solution — a pig’s kidney —Slayman told Williams he was willing to take the chance because his life was so miserable.

Slayman was a good candidate for the experiment because aside from kidney failure and diabetes, he’s in “reasonably good health” and was familiar with the transplant process, Williams said.

On Saturday, Dr. Tatsuo Kawai, director of the Legorreta Center for Clinical Transplant Tolerance at MGH, and Dr. Nahel Elias, interim chief of

The doctors removed two kidneys (with one as a backup),put them on ice, and returned by car to the hospital, where Slayman was already unconscious on the operating table.

Three surgeons operated — Elias, Kawai, and Shoko Kimura — assisted by two postdoctoral fellows, and they provided this step-by-step description of the transplant: They cut open Slayman’s lower abdomen on the left side, and attached the blood vessels of the new kidney to his, clamping them closed to avoid bleeding. At that point, the pig kidney lay pale and beigeinside Slayman’s abdomen, drained of its own blood. Then the surgeons removed the clamps, and Slayman’s blood flowed into the transplanted organ, turning it a vivid pink, suddenly alive.

The room erupted into cheers and applause. The pig kidney immediately started producing urine.

“Everybody was just elated,” Elias said.

As news of the operation spread, other doctors in the xenotransplantation field shared the excitement evinced at Mass. General.

“This is a boost to the field,” Dr. Muhammad M. Mohiuddin, president of the International Xenotransplantation Association, said in an interview Thursday.

Mohiuddin, who performed the two pig heart transplants at the University of Maryland, said he has “high hopes” for the kidney transplant, which will move the field closer to the next goal: a clinical trial involving a larger number of patients.

transplant surgery, removed the kidneys from the donor pig, which was located in another city. (For security reasons, Mass. General declined to release the location of thefacilities where they operated on the pigandwhere the pig was raised).

Dr. Jayme Locke, director of the Division of Transplantation at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, has been implanting pig kidneys in brain-dead patients. She said her team is in talks with the FDA about performing a similar operation on a living person.

“If we can keep doing this we may actually be able to eliminate the [organ transplant] waiting list and, for the first time in health care, achieve equity,” she said.

When Williams, the nephrologist, checked on Slayman on Wednesday, the patient was sitting on the edge of his bed. “He looks like his old self,” the doctor said. “Every day he’s improving from the day before.”

If he continues to thrive, Slayman will probably be discharged within the next few days. He’ll come back for tests twice a week for the first month, and may be ready to return to work in six weeks, Williams said.

If the pig kidney fails, Slayman will have to resume dialysis. He won’t lose his place on the transplant list for a human kidney. But he’s been on the list for more than two years already, and as a Black man, Williams said Slayman may havea hard time finding a kidney match.

For now, his doctors are holding onto hope amid their vigilance.

“People used to say that xenotransplantation will be the future — and always the future,” said Elias, the surgeon. “Many of us wouldn’t have thought that we could do it in our lifetime.”