When Soviet ideologues called genetics a “kept woman of imperialism,” they believed they were denouncing bourgeois pseudoscience and drawing a sharp anti-Western line. They claimed to defend the “true” purpose of biology as defined by CPSU members surrounding Trofim Lysenko, the so-called “theorist” whose “scientific ideas” later proved to be complete nonsense.

But reality, as often happens, outran their sarcasm in ways they could never have imagined. Today genetics truly has become a “kept woman” — not of capitalism, but of a far more voracious client: the global market, eager to buy your genome and immediately offer you embryos on an installment plan.

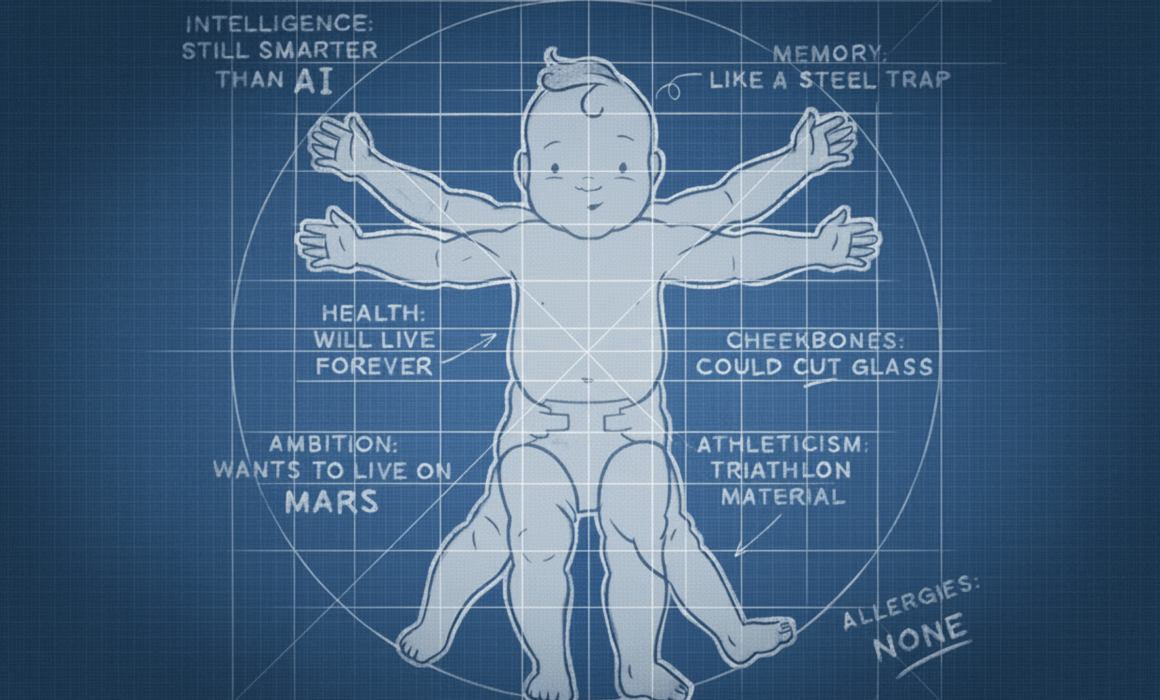

Genetics is no longer just a science. It has become the business class of humanity’s future, with premium packages, customization, risk insurance, personal-future marketing, and promises to “optimize your child.”

It all began a little more than 20 years ago, when scientists fully decoded the human genome and the world obtained a tool that still inspires cautious admiration.

Some hoped mainly for the ability to predict and prevent severe hereditary diseases. Others saw in genetics a potential means of designing a human being before birth.

At the intersection of these two approaches lies the central question: what can we actually choose when it comes to embryonic testing, and how ethical or safe is it to intervene in a life that has not yet begun, trying to forecast traits, abilities, or predispositions?

MIT Technology Review, one of the oldest and most authoritative Massachusetts-based pop-science magazines, addresses all these questions in a cyclopic text in its latest issue. The article is extensive, but here is the distilled core:

• the tools humanity currently possesses for “optimizing genes” • what these services cost and what customers they attract • whether the entire concept can be considered ethical and humane

Because it is technologically impossible to alter the DNA of an already fully developed human being, attempts to “improve” a genome focus on embryos — the stage when all cells are only beginning to form the organism.

In developed countries, the law prohibits the implantation of embryos with edited genomes into a womb. What remains for scientists is to study embryos created during IVF procedures in a laboratory and select the healthiest among them.

As MIT Technology Review notes, preimplantation testing is not new. Clinics began using it in the 1990s as part of in vitro fertilization. This approach allows parents who carry a harmful gene to have a healthy child.

Nota bene: what exactly are these PGT tests? Modern reproductive medicine relies on three established forms of preimplantation genetic testing: • PGT-A detects chromosomal abnormalities. • PGT-SR detects structural rearrangements of chromosomes. • PGT-M identifies rare monogenic hereditary diseases

PGT-M identifies rare monogenic hereditary diseases.[Разрыв обтекания текста]

However, in the early 2020s, a new tool emerged: PGT-P, or polygenic screening, which assesses the combined risk of multiple diseases and predispositions. It is also the most controversial: too ambitious, too premature, and too full of promises that it cannot yet substantiate.

This technology analyzes the simultaneous activity of hundreds of genes, as well as their interaction. This feature dramatically broadens the range of conditions detectable through a “polygenic risk score.”

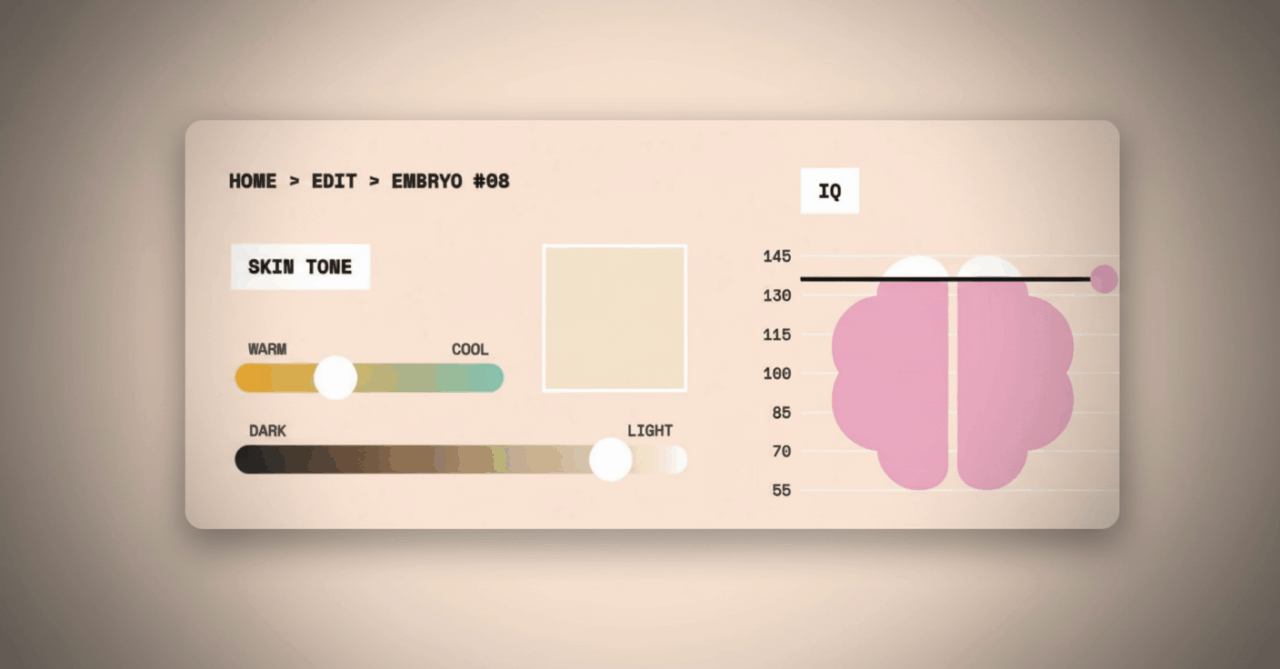

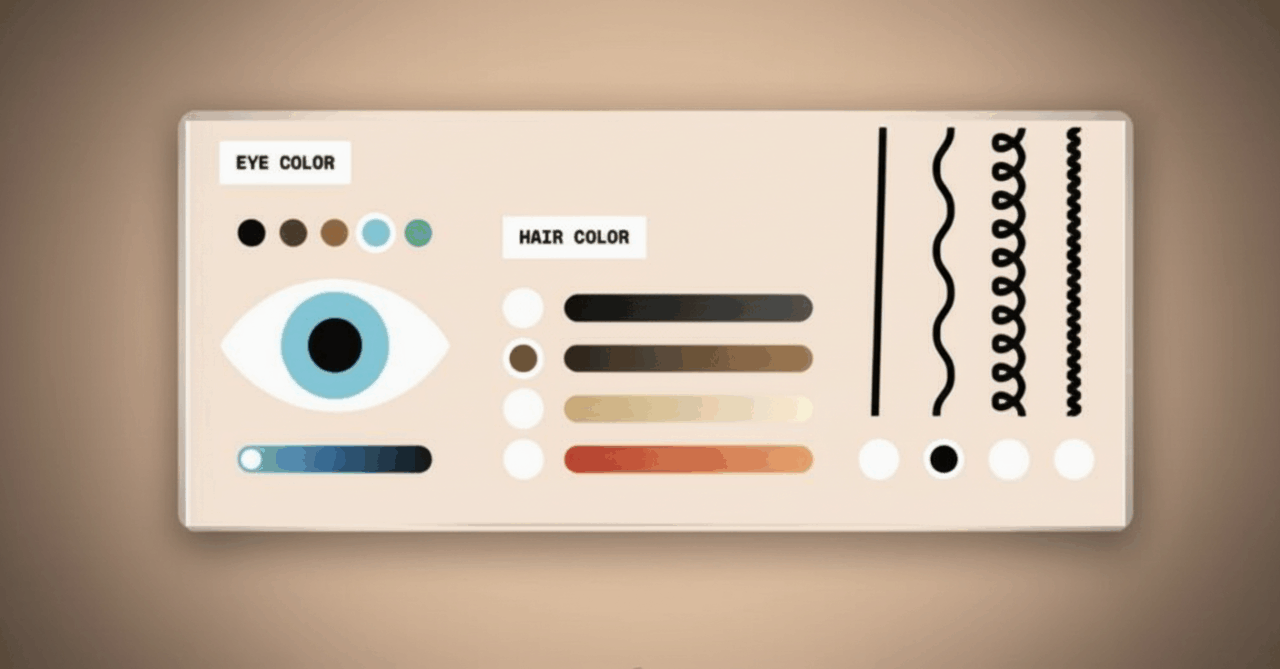

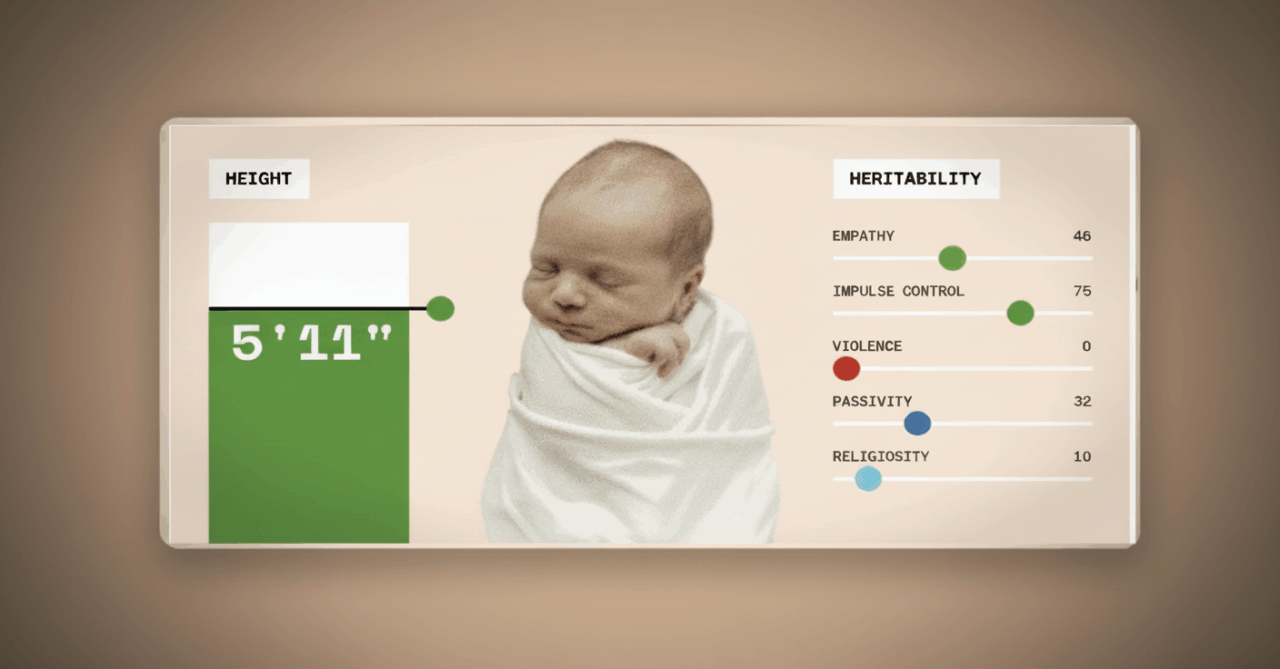

However, according to the latest trend in the genetics industry, these same tools can be used to evaluate far more complex aspects of a future human being: personality traits, potential intelligence, predisposition to disorders, aggression levels, and much more.

This is the domain targeted by ambitious new “polygenic companies” such as Nucleus Genomics and Herasight. Unlike earlier players, who were cautious in describing PGT-P’s capabilities, these firms openly claim to be developing tests capable of assessing a future child’s intelligence at the embryonic stage.

Biobanks, the large data repositories documenting how individual genes work and interact, remain the key resource for successful DNA analysis. MIT Technology Review notes that this is a point where major problems arise: science still can assess the combined activity of dozens of genes with a large number of assumptions.

Moreover, PGT-P is far from universal. Different ethnic groups have their own gene variants, which significantly influence genome behavior and analysis outcomes. Environmental factors, social conditions, and real-life circumstances also strongly shape traits.

Many scientific and regulatory institutions, including the American Society of Human Genetics and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, openly question the accuracy of PGT-P and do not recommend its implementation in clinical practice due to high uncertainty.

In 2024, the American Society of Human Genetics formulated the issue concisely: “New medical practices are developing too quickly and with too limited an evidence base.”

Once the futuristic marketing is stripped away, the business model behind most “trait tests” looks surprisingly mundane. This is not a “constructor” for assembling a superhuman from desired attributes, but more of a supermarket: several embryos are in front of you, and you choose the one that seems “most promising.”

Still, the service is expensive. According to public data and company presentations:

Nucleus Embryo, the flagship platform of Nucleus Genomics, is sold as a “lifetime subscription” for about $9,000, offering a report on roughly 2,000 traits and diseases — from diabetes risk to eye color probabilities and even “intelligence indicators.” For more extensive analysis, the company offers a screen of up to 20 embryos for $25,000+.

Competitor Herasight emphasizes precision and “premium traits.” According to its marketing materials, it provides predictions for 17 diseases and one signature metric: potential intelligence level. The company claims it can “sort embryos” with a difference of about 15 IQ points. MIT Technology Review does not verify these numbers; it only describes the industry’s growing ambition.

Thus, the market for polygenic analysis appears bold, expensive, and fragmented. It’s suspended between cautious science, aggressive PR claims, and customer demand from those wishing to “optimize” the future before it begins.

Polygenic screening primarily appeals to the technological elite, people with a certain amount of money and scientific literacy, who understand the perspective of predicting traits and predispositions. For instance, Nucleus Genomics has raised more than $36 million from Balaji Srinivasan, Seven Seven Six, Founders Fund, and other private investors.

As for the general public, MIT Technology Review cites a survey conducted among 1,627 American adults. Respondents were asked their opinion of different types of polygenic embryo testing. The results were telling:

Most supported testing for physiological diseases (heart disease, cancer, diabetes). Far fewer approved of tests for psychological disorders. And attitudes toward evaluating potential intelligence were sharply divided:

• 36.9% — positive • 40.5% — negative • 22.6% — undecided

These results align with the positions of the American Society of Human Genetics and the American Journal of Human Genetics, both of which stress that using polygenic models to predict behavioral or cognitive traits in embryos remains scientifically questionable and ethically vulnerable.

ASHG’s 2024 review states:[Разрыв обтекания текста] “Public perception of polygenic tests is strongly shaped by limited data, inflated expectations, and a very weak evidence base for cognitive traits.”

The survey suggests that humanity is still not prepared to accept such deep intervention into the phenomenon of life. Even part of the academic community has unexpectedly assumed the role of “guardians” of older concepts; criticizing supporters of polygenic testing with the same fervor Soviet “Stalinist physicists” once used to attack general relativity theory.

Nevertheless, the practical work of polygenic companies has hardly been affected — the industry has found a way to operate between scientific skepticism, ethical anxiety, and commercial enthusiasm.

Nota bene: according to ASHG and ACMG, the primary concern remains unchanged: the field is growing too rapidly with too little evidence. However, historically, these circumstances have never stopped anyone.

The strongest advocates of the method are its creators.[Разрыв обтекания текста] Nucleus Genomics founder Kian Sadeghi calls polygenic testing a technology of the future and an extension of parental freedom. If someone wants a child with blue or green eyes, in his view, that is their right. The same applies to other traits such as alcoholism risk, allergies, or acne.

Yet even the boldest companies accompany their reports with mandatory disclaimers. One of them reads:

“DNA is not a verdict and not a guarantee. Genetics can help you choose an embryo, but it cannot predict the future. This field is evolving rapidly, and much about how the genome shapes a human being remains unknown.”

The most obvious societal fear is the alleged connection between gene-optimization tools and eugenics. Eugenics, founded by Francis Galton, indeed had considerable popularity in the early 20th century, promoting the idea of “improving” a nation by encouraging “good heredity” and avoiding anything that “damaged” it.

Unfortunately, a certain German chancellor in the 1930s catastrophically misinterpreted the concept. Blending it with social Darwinism and Nietzschean “Übermensch” idea resulted in the deadliest war and ethnic cleansing in history. Hence, any modern conversation about “improving the genome” is automatically heard by many as echoes of that regime.

The topic’s sensitivity has already produced casualties.

In 2018, University of Pittsburgh professor John Anomaly, who studied social behavior, published “In Defense of Eugenics,” attempting to distinguish current practices aimed at improving quality of life from the racial doctrine of the Third Reich. His arguments were deliberately simple:

“If you don’t want siblings to have children, you are already a bit of a eugenicist. A woman choosing a sperm donor, a tall Harvard graduate, is another example.”

The American student audience, particularly active in the neo-left segment, labelled these reflections “racial essentialism.” A public outcry followed, and by 2019, Anomaly was forced out. Under pressure, he left academia entirely, later writing: “American universities have become an intellectual prison.”

Ironically, years later he joined the research team at Herasight — precisely when the company was developing its line of embryonic IQ tests.

Regulatory genetics institutions mostly remain skeptical of the method due to the weak reliability of polygenic risk scores.

The same view is shared by prominent scientists in the field. For example, Sasha Gusev, head of a genetics lab at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, has long criticized polygenic testing.

His central argument: PGT-P lacks clear clinical guarantees. Most of what it attempts to predict is heavily influenced by socioeconomic environment, geography, upbringing, personal circumstances, and many variables unrelated to the genome.

Moreover, he warns that the rapid popularization of embryonic polygenic tests for “traits” could threaten the functioning of society. People might begin to treat genetics as the primary determinant of behavior — leading to biological reductionism, with highly questionable social consequences.

What is now marketed as an exotic service for the wealthy may soon become a tool of pressure and control. Here lies the central concern: technologies that influence human life before birth will inevitably attract those who think in terms of “selection” and “management.”

For now, society still has safeguards: professional associations, ethics committees, public debate. But the decisive moment is now: will genetics remain a part of medicine and science, or will it finally turn into a constructor of “correct” human beings?

The answer to that question will determine far more than the outcome of any individual polygenic test.

Subscribe to our digest on Facebook, Instagram, Telegram – here we talk about the history and modern days of America and, first of all, about what is happening in Boston and Massachusetts.