Kaitlin Buckley and Anne-Marie Eze August 14, 2018 news.harvard.edu

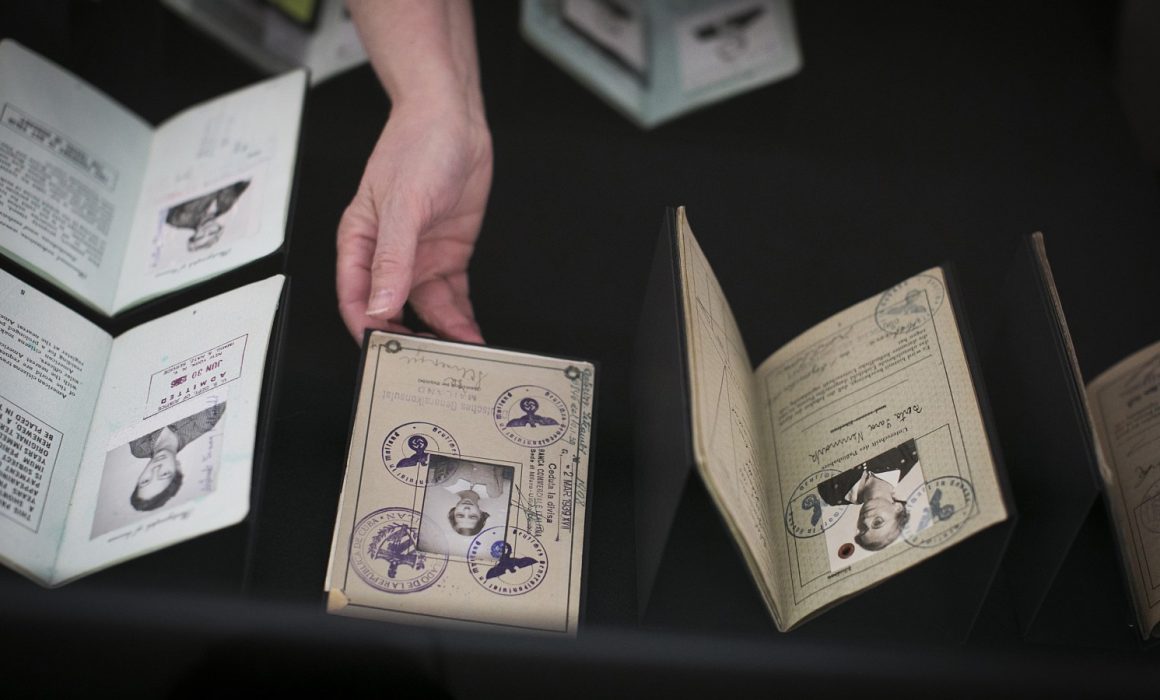

A book pierced by a bullet during the Hamidian massacres in Armenia. Leon Trotsky’s exile papers. Visas from countries that no longer exist. In “Passports: Lives in Transit,” now on display at Houghton Library, these objects — along with photographs and other travel documents — provide glimpses into the lives of the people who carried them.

“Passports speak to both the dream of finding a home outside home and the fear of never coming back,” said Lucas Mertehikian, a doctoral student in Harvard’s Department of Romance Languages and Literatures. “Both Harvard as an institution and the United States as a country have a long-standing tradition of receiving and nourishing people who desperately sought shelter throughout the past two centuries. Today, when this humanitarian mission is indeed at stake, Harvard Library serves as a reservoir in which to trace the stories of those who made it back home, and to remind us of those for whom the whole world seems equally hostile.”

Mertehikian co-curated the exhibit with classmate Rodrigo del Rio, beginning the project in late 2016. The refugee crisis, Brexit, the Trump administration’s travel bans and attempts to change DACA — as well as Professor Mariano Siskind’s seminar on migration and displacement and a workshop at Harvard’s metaLAB— prompted them to think about how to respond to these urgent global events. After surveying Harvard Library’s holdings, they proposed an exhibition. Anne-Marie Eze, Houghton Library’s director of scholarly and public programs, and Haydee Casellas, a Puerto Rican architectural designer based in Boston, helped them bring it to life.

The organizers themselves come from other countries. Mertehikian is from Argentina, where his grandparents arrived after fleeing the Armenian genocide. Del Rio is Chilean, and has traveled widely throughout Latin America. Eze is British, of Nigerian and Jamaican parentage. But the full meaning of the project sank in for del Rio as he studied the passport of George Train, the flamboyant 19th-century American entrepreneur who claimed to be the inspiration for Phileas Fogg in “Around the World in 80 Days.”

“He basically could travel anywhere he wanted,” del Rio said.

In stark contrast: Russian revolutionary Trotsky, who was constantly on the run from his political enemies. Or activists W.E.B. and Shirley Graham DuBois, who renounced their American citizenship because of government pressure.

“The cosmopolitan desire of making the whole world your home was a dream only some people could have,” del Rio said

The hands-on exhibition features materials from global travelers, immigrants, and refugees spanning the 19th and 20th centuries and drawing on collections in the Houghton, Widener, Schlesinger, Baker, and Harvard-Yenching libraries, as well as the Harvard University Archives. It is anchored by a site-specific art installation completely made of used passports Mertehikian and del Rio bought on e-commerce sites. These small bound books belonged to anonymous yet well-documented people living in the 20th century in a number of countries, including Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, and the German Democratic Republic. The stamps they bear hint at personal narratives against a background of national symbols and custom officers’ signatures.

“The passports exhibition accomplishes something fundamental to the mission of Houghton Library by showcasing how archival materials can inform and help us understand the contemporary human condition,” said Thomas Hyry, Houghton’s Florence Fearrington Librarian.

The expired documents hold no legal meaning, and are displayed as pieces of art and memory. But they are only one part of the exhibit. “Passports” also features contributions from Mertehikian and del Rio’s classmate Anthony Otey Hernández. Born in the Bronx and of Costa Rican and Greek-Chilean descent, he curated a case in honor of his mother. She died in 2017.

“My mother was an immigrant from Costa Rica, but she was also so much more,” said Otey Hernández. “She was more than her status as a ‘Permanent Resident’ and she was more than the illness that took her from me. Before her passport and before her identity as Costa Rican, she was and always will be my mother.”

See this publication in Russian